In commemoration of the 70th Anniversary of the Holocaust, a conference in Budapest considered the potential of Holocaust memorialization and memory work to serve as a catalyst for addressing discrimination today through exploring different innovative teaching practices in higher education and civic initiatives.

Heike Radvan (Amadeu Antonio Foundation) spoke about the topic “Facing current anti-Semitism, racism and neo-Nazism – talking about the Holocaust in local initiatives in East Germany”.

“In my talk today I focus on the role of Holocaust commemoration in the task of facing and counteracting current Anti-Semitism, racism and Neo-Nazism in democratic civil society. The work of the Amadeu Antonio Foundation does not focus on teaching about the Holocaust in schools or universities. It rather tries to activate and support a democratically oriented civil society, which in turn makes central the protection of minorities and criticizes all forms of discrimination and exclusion. A lively and conflict-friendly culture of debating, especially concerning the memory of the Holocaust, is a major aspect here.

In our work two arguments are especially relevant, which on first glance may seem to be contradictory, but in everyday life they coexist side by side. So the first argument: There exist many spaces in Germany where people talk about the victims of the Holocaust. But this does not mean that current forms of anti-Semitism get addressed in these same contexts. In other words and this is not a new perspective: Dealing with the past (remembering) does not necessarily imply dealing with the present (activism). On the other hand, and this is my second argument: Facing contemporary anti-Semitism, as well as neonazism and racism, is easier, if a community engages in differentiated, critical, and personal discussions about the victims of National Socialism and – importantly – at the same time, also addresses the perpetrators and their responsibility for the holocaust.

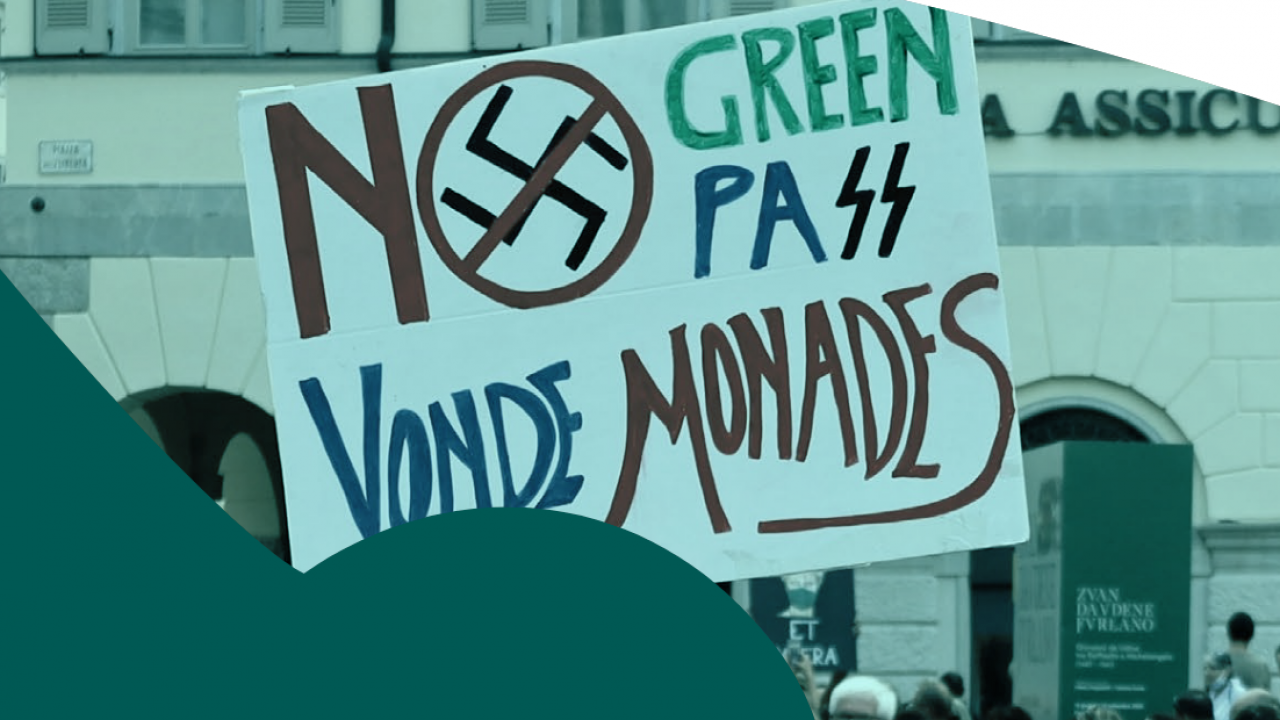

Those arguments are the results of our community based work, where we support grassroot initiatives and democratic civil society activities that oppose neonazis. Already in the 1970ies and 80ies, but especially after the German reunification in 1990, far right groups became stronger. Since the fall of the wall, Neonazis have killed approximately 184 people in Germany. We do have regions where right wing comradeships try to establish no-go areas for immigrants, left-wing, homeless and LGBTI people by threatening and violently attacking them. Especially in some areas in East Germany, Neonazi families have settled who bring their ideology into mainstream society, for instance within kindergarden. Neonazis strategically enter social work. Often right wingers, especially if they are women, are overlooked and their ideology is not recognized as what it is. One of many reasons for this is, that right-wing ideology, f.e. statements against migrant people are not a marginal problem; racist and anti-Semitic attitudes are widespread and common within the whole of society. Taking this seriously, the work of the AAF focusses on facing everyday racism and anti-Semitism.

Currently, counteracting contemporary anti-Semitism plays a significant role within our work: In the aftermath of 9/11 there was an uprising of anti-Semitic attitudes in German society, which is virulent to this day. Opinion polls and surveys reveal that historical revisionism, hostility towards Israel and (secondary) anti-Semitism are widespread in the German population. Opinion polls show that 68% of those asked agree with the statement “I get angry, that Germans even today get confronted with the holocaust”. A study from the University of Bielefeld found that 51 % of those surveyed agreed with the statement, ”What Israel today is doing to the Palestinians is in principal no different from what the Nazis did to the Jews”. Media discussions and media coverage draw upon historic and modified anti-Semitic stereotypes – today much more often and outspoken than in the 1980th as historians point out. Anti-Jewish attacks are a big threat in everyday life; people decide not to enter the street while wearing the Magen of David or a kipa. The number of anti-Semitic crimes in 2012 rose more than 70 percent in Berlin, with a nationwide jump of about 60 percent.

While academic research did face the problem in 2003 and 2004, we missed serious action within civil society: Current forms of anti-Semitism were not seen for what they are, or at least were not counteracted in many cases. So in our foundation we were thinking about how to raise awareness and support civil society action against Anti-Semitism. With our approaches we publicized two topics: local discourses about the holocaust as well as contemporary anti-Semitism. In 2003 we initiated the first supra-regional “action weeks against anti-Semitism”, which now take place every year around November 9th. On this day in 1938, anti-jewish pogroms took place in Germany, one of the steps towards the Holocaust.

Today, communities in East and West commemorate the victims of the Holocaust on this day. So we addressed those commemorative initiatives, suggesting and supporting them, beyond commemoration, to additionally analyze current developments of anti-Semitism and racism so as to actively fight these ideologies. In doing so, we did not imply a parallel of the Holocaust and contemporary Anti-Semitism. But rather, we wanted to bring attention to the current exclusion of and violence against Jews, the anti-Semitic statements against Israel and other current forms of the problem, which had been virtually absent from politics, public debates and civil society action. To do so, we did address the ways grass root and state related initiatives commemorate the holocaust. And we did point at differences between East and West Germany, which are connected to their different political pasts .

At this point I would like to summarize briefly, how the holocaust was commemorated differently in East and West Germany before reunification. The two German states commemorated the Holocaust in distinctly different ways. And these different commemorative practices have different effects on the development of a democratic civil society, particularly one which is aware of current anti-Semitism and Neonazism. Due to limitations of time, my summary will be both quite complex and probably not complex enough. But I´ll try to sharpen my argument.

Remembering the holocaust – West germany

During the 1980s, local initiatives were founded in West Germany begun asking questions what had happened exactly during the Holocaust in their regions, cities, and neighborhoods. This public discourse in West Germany had a strong focus on the prosecution and extermination of Jews. In this specific context, the German artist Gunter Demnig created the so-called “Stolpersteine”, historical monuments which commemorate victims of the Holocaust. “Stolperstein” means “stumbling block” in German. “Stolpersteine” are small, cobblestone-sized memorials for an individual victim of Nazism. They commemorate individuals – both those who died and those who survived.

During this time, there also emerged a grassroots movement called “Dig where you stand”. People who were part of this movement asked themselves questions about the places where they lived: who had lived there before? Who got victimized in the Holocaust? Who survived? This movement was connected with the social movement of 1968. Many of the people involved asked their parents what they had done during National Socialism, meaning that the debate got started in the private realm, even though it also stopped there in many cases.

These local historical debates focused almost entirely on the victims and started to deal with the perpetrators only much later. Thanks to scientific debates, publications, exhibits and documentaries those questions are discussed within specific communities. However, discussions about perpetrators in local historical contexts, so I mean small communities in rural area, are still scarce.

I would like to highlight that the discussions initiated by these local initiatives in West Germany, even though their scope was limited and narrow, were vital for the development of a democratic civil society. This means that it makes a difference whether such a local historical commemorative culture exists in a community or not. When broaching the issue of current Neonazism or anti-Semitism it is easier to find democratically-oriented persons who are interested in these developments in a community which has specifically dealt with the causes and consequences of the Holocaust. To give an example that illustrates my argument: After a desecration of a jewish cemetery in a smaller town in West Germany in 2007 quickly a group of people organized a demonstration, media reported about it, educational projects as well as a fundraising campaign to rebuild the gravestones were started. In comparison attacks on Jewish cemeteries often don´t even get noticed, much less responded in East Germany. Sometimes it is much harder to find at least one person who feels responsible. I argue that one reason for this lack of responsiveness is that in east Germany we had no commemorative culture that was locally specific and focused on specific victims and perpetrators.

This is not to deny that we still have anti-Semitic attitudes in polls covering West Germany, in fact anti-semitic criticism against Israel is widespread, and not only in leftist groups – of course this needs to be distinguished from non-antisemitic criticism of israel. But in comparison to East Germany West Germany has a more robust civil society, in which some groups are responding to current forms of neonazism, and can be approached regarding current anti-Semitism. I would like to specify this a bit more. In my work for the Amadeu Antonio Foundation I have been able to compare communities/cities in different parts of Germany. The commemorative culture I have described in West Germany so far has not existed in the same way in East Germany, where the remembrance of the Holocaust was different. There was no substantive grassroots movement, which could have started discussions about local history and responsibility. Besides a few marginalized civil-rights activists no larger contexts for discussions or movements existed that could have identified the same issues that were identified in West Germany. The memorialization of the Holocaust was ideologically biased; socialist antifascist ideology focused commemoration mainly on communist resistance fighters, while other victim groups were marginalized or not remembered at all. With its anti-capitalist point of view, the propaganda of the German Democratic Republic portrayed Israel as one of its main enemies. The revisionist media stated that what Israel was doing to the Palestinians was the same what the SS had done to the Jews—the argument that we now encounter widely in public opinion polls all over Germany. Israel got demonized and latent anti-Semitism was widespread.

So in comparison to West Germany East Germany did not have a specific and concrete remembrance culture for victims of the holocaust. During the last two decades this process has started and we are trying to support grass root initiatives to talk about questions such as: how exactly did the holocaust start, Who got victimized and who were the perpetrators?

Due to the specific and very different narratives of commemoration in East and West Germany, it is important to initiate an inner-german dialogue about questions of remembrance. To talk about this specifically, we need to face the most recent past as well and begin talking about the role of anti-Semitism within socialist East Germany and within West Germany after 1945. While there is academic research about this, there is no or little discussion about anti-Semitism in former East Germany in public discourse. To address this absence the Amadeu Antonio Foundation drafted a travelling exhibition about the topic “Anti-Semitism in the German Democratic Republic.” This exhibit initiated debates in East and West Germany about a topic hardly mentioned in public discourse before. The exhibit is called “there was not such thing as anti-Semitism within our socialist country”. We did face a lot of defensiveness in response and many questioned altogether the motivation for bringing up this important topic. Within those discussions – and this seems important concerning my argument here – we focussed specific stereotypes against jews and their modification throughout history.

As well we developed an english exhibition about racism, anti-Semitism and right-wing extremism in both German states after 1945; and the development of these phenomena after 1989.

To summarize my arguments: We need different approaches to support a lively, local and personal focused debate about the Holocaust within civil society. Beneath commemoration of different groups of victims and a personal and critic debate about perpetrators, we need to face current forms of Anti-Semitism as well as in recent past. There are different factors which are related to a vital democratic civil society, – talking about historic and current forms of anti-Semitism is one important part of it.”