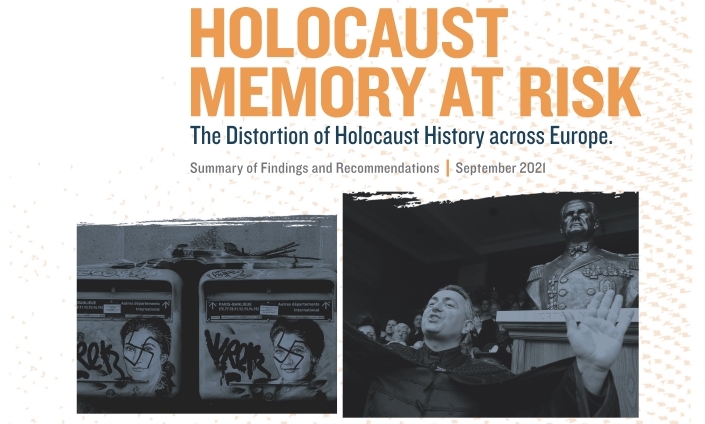

Among the most prevalent forms of Holocaust denial and distortion in Germany today are the trivialization of the Holocaust, “Holocaust fatigue,” and the issue of “double-genocide,” the equation of Nazi and Communist crimes. Other noticeable aspects of distortion consist of inaccurate comparisons between Israel and Nazi Germany or Zionism with Nazism. While specifically German in some respects, these developments go along with international trends. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s report, to which the Amadeu Antonio Foundation contributed, looks at these and other forms of Holocaust distortion and the politicization of history across Europe.

Download the summary here.

Germany’s role in the Holocaust

Following Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, Nazi Germany initiated and pursued policies that led to the systematic persecution and ultimately mass murder of Europe’s Jews. Driven by extremist racist and antisemitic ideology, Nazi Germany continued to kill Jews up to the very moment it was defeated by the Allies in May 1945. By this stage some 6 million Jews, about 2/3rds of the entire Jewish population in Europe, had been murdered as part of Hitler’s genocidal program. Additionally, the regime killed several hundred thousand Roma and Sinti, more than 200,000 persons with mental and/or physical disabilities, between 2 and 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war, about 1.9 million non-Jewish Poles, and brutally persecuted political opponents, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others.

The evolution of postwar historical narratives

The case of Germany differs in major ways from other European nations. Following Nazi Germany’s defeat in May 1945, the Allies made a concerted effort to confront the German population with Nazi crimes. Local townspeople were taken to the newly liberated concentration camps to see the evidence of Nazi crimes that took place in their backyards. Films, posters, brochures, and other printed materials showing images from these camps were widely distributed particularly in the immediate aftermath of the war.

Trials of Nazi war criminals followed, especially the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which prosecuted Germany’s political and military leadership for participating in a conspiracy to wage a war of aggression, war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. The proceedings were disseminated widely in the press and in newsreels to highlight German government’s responsibility for launching World War II and the mass murder of Europe’s Jews as well as many other crimes.

Lesser trials were conducted in each of the four occupation zones, including those focusing on concentration camp commandants and guards. The Subsequent Nuremberg Trials carried out by US military tribunals outlined the responsibility of physicians, industrialists, jurists, military leaders, and government agencies, including the German Foreign Office, for Nazi crimes.

Post-war Germany consisted of two separate states, the Federal Republic of Germany in the West and the German Democratic Republic in the East, from 1949 to 1989. As a result, the historical narratives of the German past were radically different with the German Democratic Republic sharing many politicized historical perspectives with its fellow members of the Soviet bloc. In the politically charged atmosphere of the Cold War, East German polemics often derided West Germany for being a bastion of fascism that permitted former Nazi officials to shape postwar governmental policies.

During the Communist Period

In the German Democratic Republic memories of Nazi rule were kept alive and instrumentalized for political purposes, both to present East Germany as the true democratic state untainted by Nazism and to glorify the Communist resistance to Nazism. As in other Soviet bloc nations, memorials at former Nazi camps served to overemphasize the role of the political opponents, especially Communists, while downplaying the experiences of other victim groups. The persecution and mass murder of Europe’s Jews was not denied but it was not the principal feature of East German commemoration.

West Germany

The national narrative in the Federal Republic of Germany took a different emphasis, also driven in part by the politics of the Cold War. In the early decades, there was a consensus that emphasized the responsibility of Adolf Hitler, the Nazi Party, and the SS for the German crimes committed in the 1930s and 1940s. There was also a consensus among the major political parties already in the 1950s to initiate restitution to Jewish victims of Nazi persecution through payments. Subsequent legislation over the decades expanded the payments to other victim groups. The German Democratic Republic did not participate in this program.

The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial in the 1960s as well as the earlier Eichmann Trial in Israel opened the eyes of a new generation to Nazi crimes. In 1979, the broadcast of the US made-for-television series, Holocaust, generated vigorous debate.

National narrative since German reunification

In recent decades, the German national narrative has been challenged and altered. Beginning in 1995, an exhibition on the role of the Wehrmacht undermined the widespread belief in the untainted history of the German military during the Third Reich. It fueled a vigorous and heated debate among scholars and the public, but New scholarship focusing on the history of the nation’s Jewish communities, the involvement of key professions, government agencies, and businesses in Nazi crimes, and the role of ordinary Germans in “Aryanization” or looting of Jewish property or in mass murder has generated intensive national soul-searching and reflection.

Commemoration and Responsibility

Germany marks the Holocaust on January 27, the day when the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and killing center was liberated by the Red Army. The commemoration was first introduced in 1996 and is officially called Memory Day for the Victims of National-Socialism. The ceremony is marked in the parliament and in many towns and local communities throughout the country, usually at monuments erected in memory of the victims.

The Roma and Sinti Holocaust is additionally commemorated on August 2, the anniversary of the day when more than 2,000 Roma and Sinti prisoners at Auschwitz-Birkenau were sent to the gas chambers in 1944.

A related commemoration day officially marked is November 9, the day of the 1938 pogrom known as “Crystal Night”, when Nazis torched synagogues, vandalized Jewish homes, schools and businesses and killed close to 100 Jews. This day, however, coincides with the date of the fall of the Berlin Wall–– symbol of the reunification between East and West Germany. This fact created an overlap, sometimes also a competition of remembrance.

Holocaust Research and Education

Holocaust research in Germany has made considerable progress and historians now have access to a broad range of reliable resources and expertise, particularly after the launch of the Center for Holocaust Studies at the Institute for Contemporary History in Munich. In Berlin, the Topography of Terror Foundation and the Jewish Museum are the primary institutions addressing public education, engagement, and research opportunities, in addition to university programs.

Germany’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe lies in the heart of the nation’s capital, Berlin, opened on May 8, 2005, the 60th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe. More than 450,000 visitors per year visit the site and its information center.

In addition, Germany conserves over 2,000 memorial sites bearing witness to the horrors perpetrated by the Nazi regime, including at former concentration camps, such as Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen.

Grassroots commemoration

At the local level, German communities have tried to address the Nazi past in their own neighborhoods. One such successful initiative, the so-called Stumbling Stones, originated in Cologne in 1992 by German artist Gunter Demnig and were first placed in Berlin in 1996. The Stumbling Stones are small concrete cubes (10 by 10 centimeters, 3.9 in × 3.9 in) bearing a brass plate inscribed with the name and life dates of victims of Nazi extermination or persecution inserted into the pavement at their last place of residency or work. The initiative spread all over Germany and crossed borders into Austria, the Netherlands and twenty other European countries. They have been described as “the largest decentralized monument in the world.” (Anne Thomas, Deutsche Welle, 2016)

Laws against Holocaust Denial

Germany has strict laws banning the dissemination of Nazi symbols and propaganda that date back to the immediate postwar era. Like many other European nations, it also prohibits the denial of the Holocaust. Since 1985, the German Penal Code has banned Holocaust denial. In 1994, Holocaust denial was included in more extensive anti-incitement legislation. Not only outright denial, but trivialization of the Holocaust, along with approval of Nazism can result in imprisonment for up to 5 years for an individual found guilty of exposing such views in public or assembly. In more recent years, the German government has taken steps to expand such legislation to the internet and social media. The German government has the legal right to shut down websites sponsored by organizations banned as a threat to the republic, those that promote Nazism, incite racial, religious, or other forms of hate speech, or those that spread Holocaust denial.

In response to the rise of neo-Nazism, the Federal government has expanded the number of banned symbols and slogans to include those of far-right extremist organizations.

Education

Facing its past proved to be a difficult process for Germans but one that many argue has been exemplary, particularly in comparison with other nations around the globe. The Holocaust is taught extensively at different levels in educational system. In addition, Germany has a robust scholarly community that has not only investigated the multitude of Nazi crimes, the participation of ordinary Germans in the persecution and destruction of European Jewry and other victim groups, but has documented, both at a national and local level, the important role that Jews played in their community.

Responsibility for school education lies with the governments of Germany’s 16 federal states. The Standing Conference of State Education Ministers is responsible for curriculum co-ordination. This explains why on the subject of the Holocaust (unlike other subjects) school curricula throughout Germany are very similar. At different stages the Holocaust must be covered extensively in history and politics/social classes (civic education) and may also feature in German literature, religion or ethics classes. Aspects of Holocaust history may also be dealt with in biology, art and music classes. Thus, the teaching of the Holocaust in schools is not restricted to just one field of study, being addressed from a variety of angles and approaches. History curricula address National Socialism and the Holocaust in the ninth and tenth grades, as well as in the eleventh and twelfth graders of upper secondary school.

Impact of Public Education Efforts

An international study published in 2015 confirms that Germany is the country where the Holocaust figures in textbooks most times worldwide. Looking at the German curricula evaluated in this study, it becomes clear that the Holocaust is not only taught in history lessons but also in interdisciplinary modalities as well as participatory ones. The curricula provide for the participation of students in the development of the contents. Another study (also published in 2015) based on teachers’ responses showed that the Holocaust occupies a very central role in the teaching of history. The Nazi era in general appears as one of the most important, if not the most important, topic in history education. Nevertheless, the patterns of assessment and perception vary regarding how appropriate teaching is to be designed and how to deal with this chapter of German history.

Evaluating tertiary (university) education poses some problems and Germany’s record seems rather mixed. On one hand, German university professors in the field have inspired younger scholars to pursue research in this field, yet on the other hand, the number of courses offered at German universities on the Holocaust or Nazi Germany seems limited. A recent study by the Free University of Berlin showed that every fifth German university offers only one (or no) course on the years 1933 to 1945 within the four semesters equivalent of a B.A. degree. Almost twice as many courses exist on the aftermath of National Socialism and its genocide. Only a few universities regularly teach basic knowledge courses on the Holocaust.

Contemporary Manifestations of Holocaust Distortion and Related Politicization of History

Trivialization of the Holocaust

While outright denial of the Holocaust seems to have relatively few adherents in Germany, some political leaders from rightist parties have tended to minimize the importance of Nazi Germany and with it the Holocaust. In early June 2018, one of the group leaders of the right-wing populist AfD described National Socialism (NS) as “bird shit” within the 1,000-year history of Germany. He later distanced himself from it, claiming his intention had been to make just a qualitative evaluation of National Socialism. Before the 2017 federal elections, an AfD candidate and judge declared the German “cult of guilt” as “finally over.” Another top AfD elections candidate said Germany should no longer be “reproached” for what its soldiers did in the Second World War. On the contrary, “we have the right to be proud of the achievements of German soldiers in two world wars.”

Holocaust Fatigue

There are also signs of what has been called “Holocaust fatigue” or “saturation.” In 1998, this phenomenon was aptly expressed in a speech delivered upon the acceptance of the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade in Frankfurt. Writer Martin Walser spoke of “the historical burden, the never ending shame” daily presented to Germans in one way or another. When that happens, he said, “I notice that something inside me is opposing this permanent show of our shame.” And instead of being grateful for the reminder, “start looking away.” What prompted that reaction, he explained, was not a refusal to face the German past, but rather “the exploitation of our shame for current goals. Always for the right purpose, for sure. But yet exploitation …Auschwitz is not suitable for becoming …an always-available intimidation or a moral bludgeon or also just an obligation. What is produced by ritualization has the quality of a lip service.”

Although Walser comments triggered condemnation from some circles, the problem of “Holocaust saturation” is a real one for all engaged in Holocaust education–– and not only in Germany.

In recent years, politicians from Germany’s growing alt-right movement have openly complained about German memory culture. In a speech in January 2017 an AfD politician declared that the “Germans are the only people who have a monument of shame planted in their hearts.” In an open letter an AfD Baden-Württemberg state parliament member called for ending the stumbling stones memorialization, imposed, as he wrote, by “penetrating moralists.”

Comparative Victimhood

While this phenomenon is not as widespread in Germany as it is in other parts of Europe, it too has its adherents. On public television, documentaries are often shown, in which the personal role of Adolf Hitler is overemphasized. He appears as the Austrian seducer of the nation, while neglecting individual participation in National Socialism and Holocaust.

The memory of the bombardments of German cities by the Allies is specifically used by right-wing extremists to relativize Nazi war crimes by placing them on the same footing with alleged Allied war crimes. For example, the term, “Bombholocaust,” is used, among other occasions, during the annual demonstration in Dresden for the anniversary of the air raids. In 2017, “stumbling stones” that had been laid in memory of Jewish deportees under National Socialism were defaced with the names of victims of the February 1945 bombing of Dresden.

The Federation of German expellees in the Federal Republic of Germany (BdV), an organization claiming to represent the interests of the millions of ethnic Germans who were forced to leave their homes in Central and Eastern Europe after the Nazi defeat, plays a significant role in this self-victimization. By the 1980s, for example, more than 1,500 so-called “expellee monuments” had been created on the initiative of expellee associations, accompanied by the political demand for the “lost” territories to be returned. Nazi crimes or German guilt at the root of causes of the postwar expulsions are not discussed. In its “Chronicle of the Expulsions of European Peoples in the 20th Century,” the “Center against Expulsions” founded in 2000 by the BdV lists the victims of the Holocaust together with the Germans expelled.

Double-Genocide Myth

As in other countries that fell under Soviet rule after 1945, as did the eastern part of Germany, the Federal Republic has its share of politicians and others who equate Nazi and Communist crimes, a comparison that Michael Shafir has called “Double-Genocide”–“Holocaust Obfuscation–Competitive Martyrdom.” Joachim Gauck, later president of Germany from 2012 to 2017, contributed to the German edition of the controversial Black Book of Communism , whose editor, Stéphane Courtois, puts the crimes of the two totalitarian regimes on the same footing. In his contribution to this volume, Gauck pronounced himself against “exaggerating” the Shoah into an event whose uniqueness was beyond doubt.

The equation of crimes of National Socialism and Stalinism can be found in political debates and parts of research and commemoration politics in Germany. It is also partly reflected in state memorial laws in East Germany. Thus, the Saxon memorials have the task of commemorating “victims of political tyranny” from 1933 to 1989 without trivializing the Nazi regime or distorting the Holocaust. Critics accuse Saxon memorials in particular of interpreting and implementing this to equate crimes of National Socialism and Stalinism or the GDR.

As of late, there are increased attempts to achieve the equation of crimes of National Socialism and Stalinism in public discourse. For example, on January 27, 2015, the Thuringian state parliament faction of the AfD wanted to lay a wreath at the Buchenwald concentration camp memorial to commemorate victims of Nazi and Stalinism together. The attempt was stopped by the memorial’s administration.

Myth of Judeo-Communism

Another facet of the “Double Genocide” theory emphasizes the alleged Jewish origins of the communist idea and its implementation. This is the myth of Judeo-Communism. AfD protagonists have somewhat updated the myth and nowadays speak about the dangers of “cultural Marxism” allegedly spread by intellectuals and university elites. By and large, this is coded antisemitism, utilized also in order to ward off sanctions.

Holocaust Distortion and Social Media

The German government has taken aggressive steps in recent years to combat online Holocaust denial and antisemitism. In January 2018, the country’s Justice Ministry ordered Facebook to comply with the nation’s legislation regarding Holocaust denial and take down accounts promoting such views or face heavy fines for non-compliance. That same year, researchers at Berlin’s Technical University revealed that antisemitic content in German social media had increased from 7.5 % in 2007 to more than 30 % in 2017.

Antisemitic attacks

About 200,000 Jews currently reside in Germany, the vast majority of whom are emigres from the former Soviet Union. According to the 2017 US State Department Human Rights Report, antisemitic incidents, including verbal and physical assaults, have occurred as well as desecrations of Jewish cemeteries and Holocaust memorials. According to German officials most of these have been committed by neo-Nazis and other far-right organizations or individuals, while Jewish groups report increases in antisemitic attitudes among some Muslim groups. In 2016 a reported 644 antisemitic crimes took place in Germany and that antisemitism was manifest, not just on the far right, but among extreme leftist and Muslims in the country.

Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism

Holocaust distortion, however, is not just manifested in the statements of the extreme right in Germany. Sometimes leftist figures distort the Holocaust by linking it the current conflict between Israel and the Palestinians or falsely comparing Zionism with Nazism. Several art performances were criticized in recent years for what critics viewed as Holocaust distortion. At the end of 2016, a work of art was shown at the Art.Fair in Cologne, in which, depending on the angle of view, either a Swastika or a Star of David could be seen. The artist justified his work by saying he wanted to show how ideologies often misuse symbols for religious or political ends.

The equation of Israeli policy in the occupied territories with National Socialism is a widespread form of guilt defense in Germany. According to studies by Bielefeld University, slightly more than 27 % of Germans agreed in 2014 with the statement “What the State of Israel does to Palestinians today is in principle not different from what the Nazis did to the Jews during the Third Reich.” In 2016, the proportion had dropped somewhat, but is still close to one quarter of the German population (24.6 %).

Democratic Values and Institutions

In spite of the upsurge of populist and alt-right sentiment, Germany remains a full-fledged democracy, committed to maintaining the civil rights and freedoms of all its citizens. That being said in recent years several scandals involving the German military and the police have raised questions. In 2017, investigators reportedly discovered 275 cases among Bundeswehr soldiers of Nazi sympathies, such as displaying the Hitler salute or mouthing antisemitic slogans. The following year this grew to 431. Holocaust memory and education is needed more than ever.